Using Coins in Early America

The top reasons for my enjoyment of coin collecting is the history of coinage, the coin designs over time, and imagining who or how the coins have been used in the past. I have read some books about coinage throughout the world and read early United States legislation about coinage but none of those gave practical insight into people's day-to-day lives in early America.

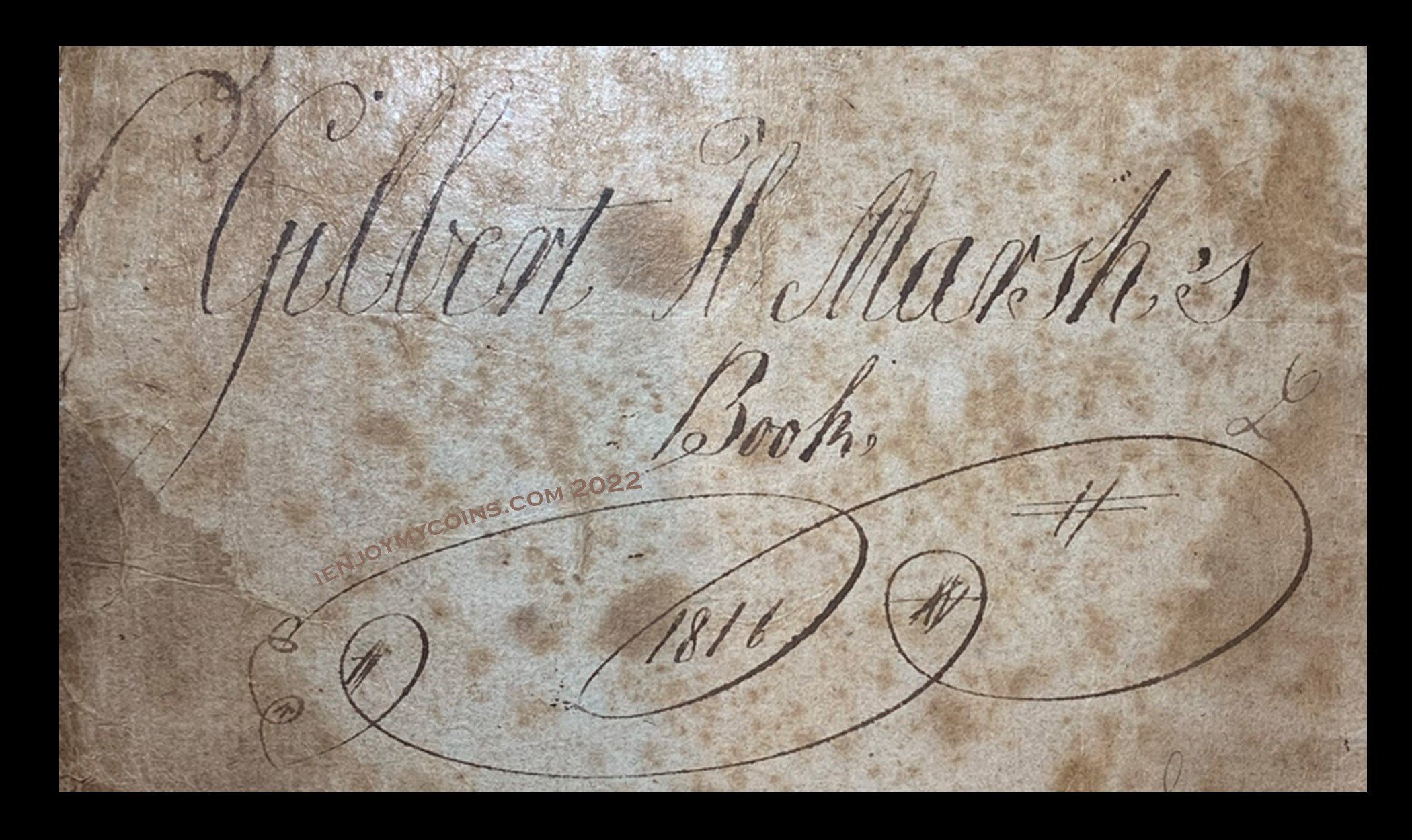

I was extremely fortunate to find a math book written by an ancestor of mine during his school days starting in 1816. Gilbert Marsh 1816 Book Cover

That book gave some wonderful insight of people using coins in early America. I'm excited to share some of the most interesting excerpts with you.

What US Currency was Circulating?

A seemingly straightforward question is more complex than it first sounds. The easy answer would be United States half cents, cents, half dimes, dimes, quarters, half dollars, dollars, quarter eagle (gold $2.50), half eagle (gold $5), and eagles (gold $10).

That answer ignores the plethora of colonial and post-colonial coins that each had their own values that were close to but not always the same value as the US issued currencies. For the purpose of this narrative, I'll exclude this broad category and focus just on the first list.

Now, the lowest value coin was the half cent but that wasn't the base unit of US money. That distinction was given to the mill. It seems odd today since I had never heard the term, but after being exposed to it for a while the unit started to show up in several places. The most common today is the 3rd decimal place on a gas pump. In those days, the resulting purchase price was rounded to the half cent for commerce.

Gilbert wrote the below table to show the multiples of 10 that made easy calculation for Federal currency (US currency). Ten mills to the cent, ten cents to the dime, ten dimes to the dollar and ten dollars to the eagle. That base made the currency much easier to use than the Great Britain pound, shilling, penny, and farthing coins that were used in the day.

My favorite quote of Federal Money is "Of all coins this is the most simple, and the operations in it the most easy." That implies a pride in the currency of his country and leads into some of the examples later in the book.

Were Any Other Currencies Used?

The United States being a new country, there were still large amounts of coin circulating from Europe as well as coins from the Spanish territories to the south. Similar to what I did previously, I'll simplify to the most common foreign coins that were circulating in Thomaston at that time - coins from England.

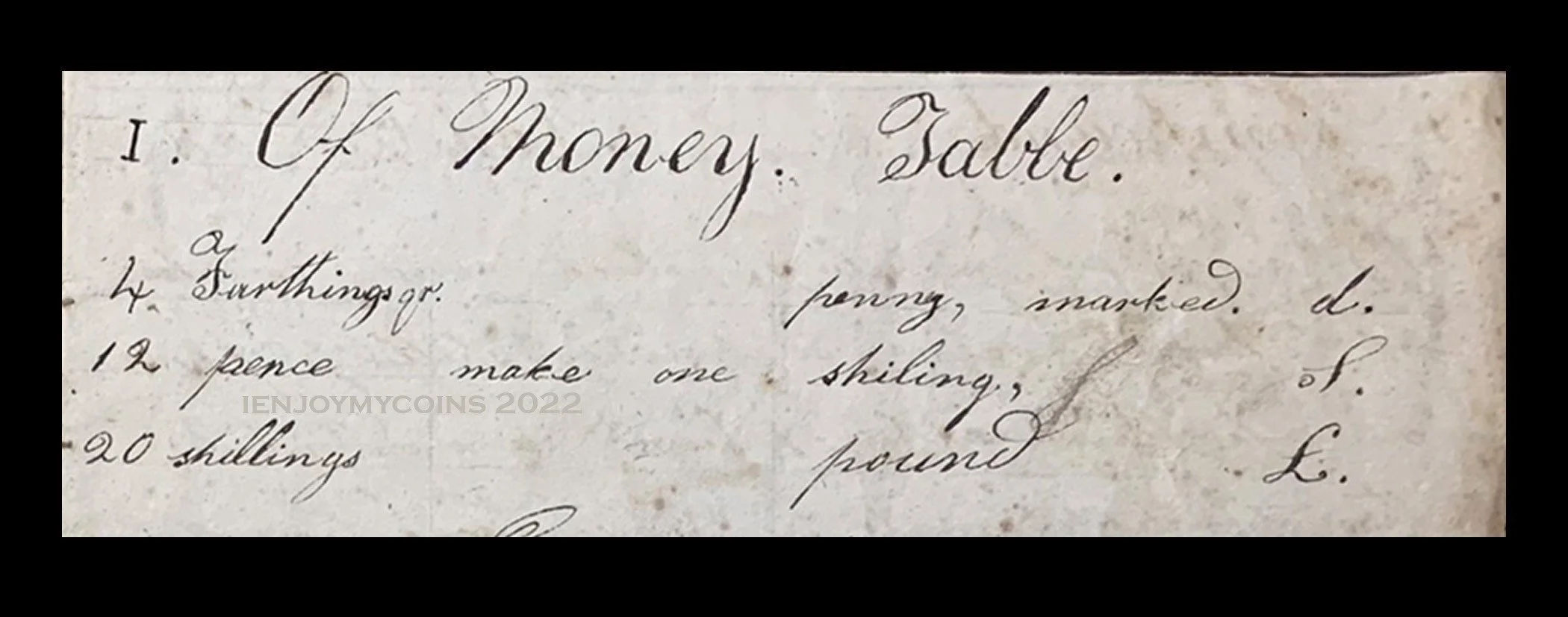

The coins were the farthing, half penny, penny, threepence, sixpence, shilling, half crown, crown, and pound. Those coins represented different values that were mostly calculated in farthings, pennies, shillings, and pounds.

Pound Shilling Penny Summary

Unlike the base 10 for Federal coin, there were 4 farthings to the penny, 12 pennies to the shilling, 5 shillings to the crown, and 4 crowns to the pound.

How Did Businesses Operate with Multiple Currencies

My first reading of the examples in Gilbert's math book really showed the complexity of completing transactions at that point in time compared with today.

The fishing industry has always been important in coastal Maine, so starting with an example of a codfish merchant seems quite applicable. This picture shows a different measuring system than we use today as well as the fees that were considered in early 19th century America.1816 Codfish Pricing

Aside from the number of decimal places, the unit of weight and the mathematical operators were also written differently.

Converting Between Currencies - The Rule of Three

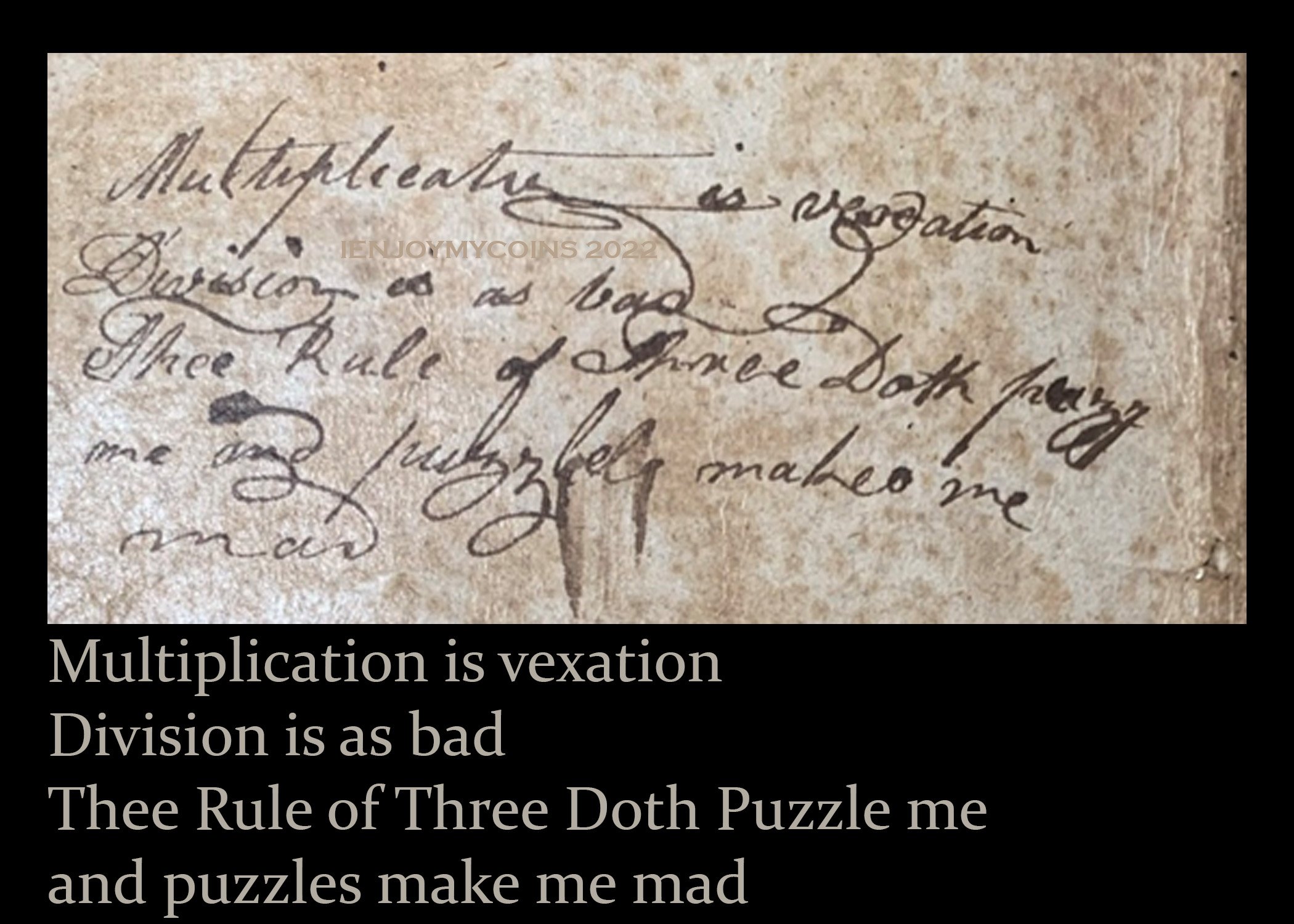

The note inside the cover is a perfect way to start this section "Multiplication is vexation, Division is as bad, Thee Rule of Three Doth puzzle me, and puzzles make me mad".

I'm no stranger to mathematics with an undergraduate minor in math but the Rule of Three did puzzle me and require multiple iterations to even follow. This conversion rule is based on the rule of three and it's application to currency and coin exchange.

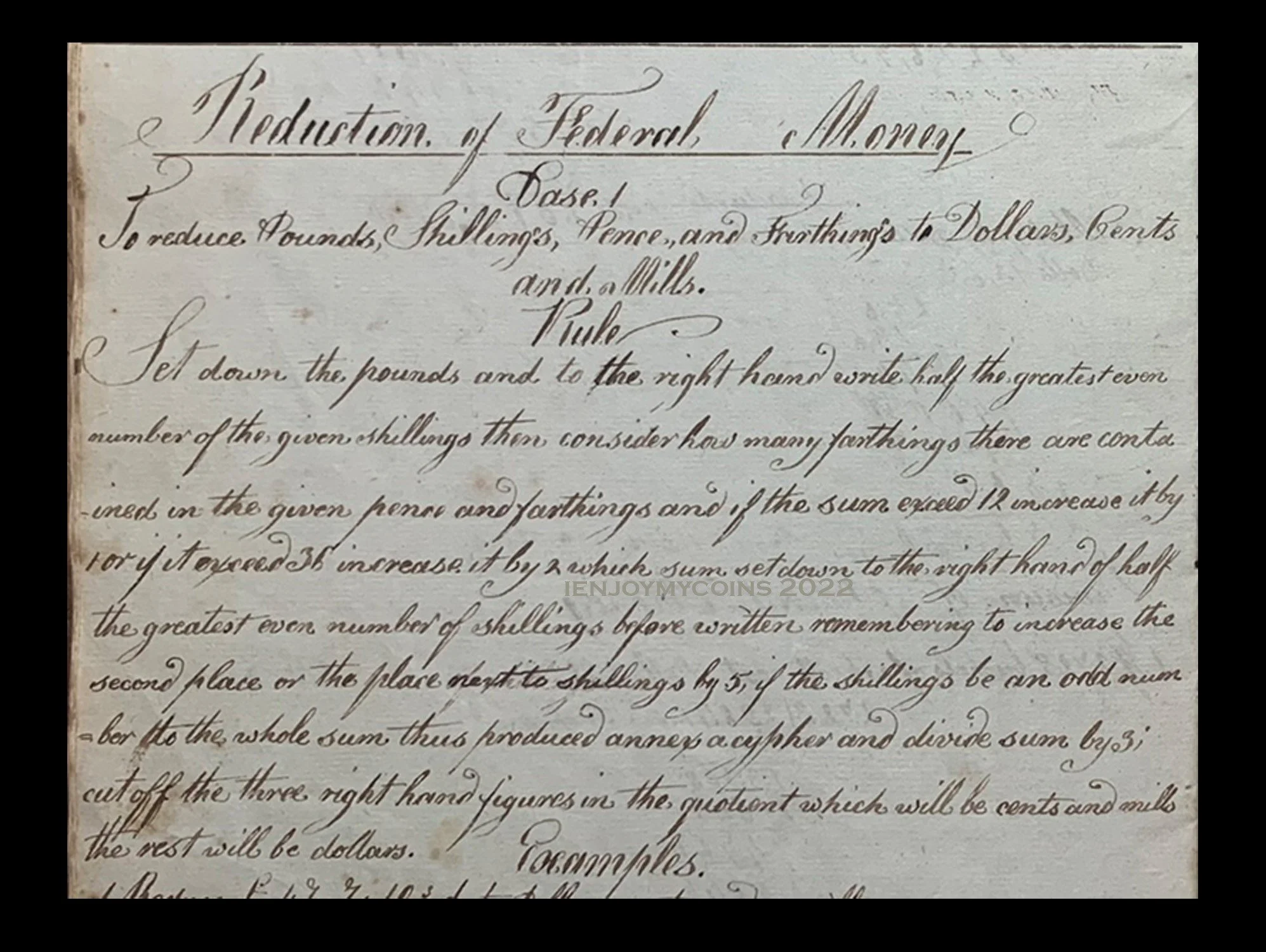

Converting Federal Money to L, S, and d

There is a conversion given in the opposite direction too - also based on the Rule of Three. Converting L, S and d to Federal

Much of the book is dedicated to examples requesting total prices when given unit prices for land, fabric and other commodities. There are also examples that convert between currencies. Further yet, there are questions about provisions for garrisons, interest on loans, and resolving debt. Below are a few more examples in both currencies - I did note that the cost per unit was not the same when converted from Federal coin and pound, shilling, pence, and farthings.

Weights and Measures

Strictly because I found it interesting, we'll see a couple of my favorite tables in Gilbert's math book. Those are the conversions for standard weights at the time. This first one tells what a quintal (or quarter listed below) actually is. The long ton of 2,240 lb actually makes sense with this added unit.

Avoirdupois Weight Summary

Now, let's link back to the coin theme and get into the troy weight system. Once again, I'll have to admit that I was thrown off by the troy pound being 12 troy ounces since I've always used 16 oz to a pound in the rest of my life. "By troy weight are weighted gold, silver, jewels, electuaries and liquors." Once again, understanding the list required a dictionary to find that electuaries are powdered medicines mixed with honey to make them consumable.

Appreciating the Difficulty of Finance in 1816

There are so many directions that these examples might take us so I started with a quick overview with the quotes and examples I found most interesting and applicable to the ienjoymycoins readers. I hope you found this look at the early 19th century coin and currency conversion as interesting and enjoyable as I do.

With just one currency being exchanged in the United States today, it's hard to picture a time when this was necessary. These examples show that it absolutely was necessary to understand math principles, the fixed exchange rate between currencies made teaching these conversions possible (without the internet), and I can just imagine a shop keeper in 1816 doing these calculations by hand when making a large sale to a good customer.

Keeping track of the transactions was surely hard, but their practice and skill made it possible. I'll leave you with the quote from earlier in Gilman Marsh's penmanship.